The Hershel Partnership

Though I have lived in Slough for many years.. for some reason, or other I have not taken any real interest in William Herschel who discovered the planet Uranus, and made many important contributions to Astronomy. His sister Caroline acted essentially as his helper in his work, and she like her brother deserves some acclaim. She was the first salaried female astronomer in the history of science. In the Library in Slough I have been reading an excellent, and readable book entitled The Hershel Partnership. An account notably from the POV of Caroline herself ...(pic/Amazon)

William Herschel

William Herschel | |

|---|---|

1785 portrait by Lemuel Francis Abbott | |

| Born | Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel 15 November 1738 |

| Died | 25 August 1822 (aged 83) Slough, England |

| Resting place | St Laurence's Church, Slough |

| Nationality | Hanoverian; since 1793 British[1] |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) | Mary Baldwin Herschel |

| Children | John Herschel (son) |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1781) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy and music |

| Signature | |

Sir Frederick William Herschel[2][3] KH, FRS (/ˈhɜːrʃəl, ˈhɛər-/;[4] German: Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel; 15 November 1738 – 25 August 1822) was a German-born British[5] astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline Lucretia Herschel (1750–1848). Born in the Electorate of Hanover, William Herschel followed his father into the military band of Hanover, before emigrating to Great Britain in 1757 at the age of nineteen.

Herschel constructed his first large telescope in 1774, after which he spent nine years carrying out sky surveys to investigate double stars. Herschel published catalogues of nebulae in 1802 (2,500 objects) and in 1820 (5,000 objects). The resolving power of the Herschel telescopes revealed that many objects called nebulae in the Messier catalogue were actually clusters of stars. On 13 March 1781 while making observations he made note of a new object in the constellation of Gemini. This would, after several weeks of verification and consultation with other astronomers, be confirmed to be a new planet, eventually given the name of Uranus. This was the first planet to be discovered since antiquity, and Herschel became famous overnight. As a result of this discovery, George III appointed him Court Astronomer. He was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society and grants were provided for the construction of new telescopes.

Herschel pioneered the use of astronomical spectrophotometry, using prisms and temperature measuring equipment to measure the wavelength distribution of stellar spectra. In the course of these investigations, Herschel discovered infrared radiation.[6] Other work included an improved determination of the rotation period of Mars,[7] the discovery that the Martian polar caps vary seasonally, the discovery of Titania and Oberon (moons of Uranus) and Enceladus and Mimas (moons of Saturn). Herschel was made a Knight of the Royal Guelphic Order in 1816. He was the first President of the Royal Astronomical Society when it was founded in 1820. He died in August 1822, and his work was continued by his only son, John Herschel.

Early life and musical activities[edit]

Herschel was born in the Electorate of Hanover in Germany, then part of the Holy Roman Empire, one of ten children of Issak Herschel and his wife Anna Ilse Moritzen, of German Lutheran ancestry. His forefathers came from Pirna, in Saxony. Theories that they were Protestants from Bohemia have been questioned by Hamel,[citation needed] since the surname Herschel already occurs a century earlier in the very same area that the family lived in.

Herschel's father was an oboist in the Hanover Military Band. In 1755 the Hanoverian Guards regiment, in whose band Wilhelm and his brother Jakob were engaged as oboists, was ordered to England. At the time the crowns of Great Britain and Hanover were united under King George II. As the threat of war with France loomed, the Hanoverian Guards were recalled from England to defend Hanover. After they were defeated at the Battle of Hastenbeck, Herschel's father Isaak sent his two sons to seek refuge in England in late 1757. Although his older brother Jakob had received his dismissal from the Hanoverian Guards, Wilhelm was accused of desertion[8] (for which he was pardoned by George III in 1782).[9]

Wilhelm, nineteen years old at this time, was a quick student of the English language. In England he went by the English rendition of his name, Frederick William Herschel.

In addition to the oboe, he played the violin and harpsichord and later the organ.[10] He composed numerous musical works, including 24 symphonies and many concertos, as well as some church music.[11] Six of his symphonies were recorded in April 2002 by the London Mozart Players, conducted by Matthias Bamert (Chandos 10048).[12]

Herschel moved to Sunderland in 1761 when Charles Avison engaged him as first violin and soloist for his Newcastle orchestra, where he played for one season. In "Sunderland in the County of Durh: apprill [sic] 20th 1761" he wrote his Symphony No. 8 in C Minor. He was head of the Durham Militia band from 1760 to 1761.[13] He visited the home of Sir Ralph Milbanke at Halnaby Hall near Darlington in 1760,[14]: 14 where he wrote two symphonies, as well as giving performances himself. After Newcastle, he moved to Leeds and Halifax where he was the first organist at St John the Baptist church (now Halifax Minster).[15]: 411

In 1766, Herschel became organist of the Octagon Chapel, Bath, a fashionable chapel in a well-known spa, in which city he was also Director of Public Concerts.[16] He was appointed as the organist in 1766 and gave his introductory concert on 1 January 1767. As the organ was still incomplete, he showed off his versatility by performing his own compositions including a violin concerto, an oboe concerto and a harpsichord sonata.[17] On 4 October 1767, he performed on the organ for the official opening of the Octagon Chapel.[18]

His sister Caroline arrived in England on 24 August 1772 to live with William in New King Street, Bath.[2]: 1–25 The house they shared is now the location of the Herschel Museum of Astronomy.[19] Herschel's brothers Dietrich, Alexander and Jakob (1734–1792) also appeared as musicians of Bath.[20] In 1780, Herschel was appointed director of the Bath orchestra, with his sister often appearing as soprano soloist.[21][22]

Astronomy[edit]

Herschel's reading in natural philosophy during the 1770s indicates his personal interests but also suggests an intention to be upwardly mobile socially and professionally. He was well-positioned to engage with eighteenth-century "philosophical Gentleman" or philomaths, of wide-ranging logical and practical tastes.[22] Herschel's intellectual curiosity and interest in music eventually led him to astronomy. After reading Robert Smith's Harmonics, or the Philosophy of Musical Sounds (1749), he took up Smith's A Compleat System of Opticks (1738), which described techniques of telescope construction.[23] He also read James Ferguson's Astronomy explained upon Sir Isaac Newton's principles and made easy to those who have not studied mathematics (1756) and William Emerson's The elements of trigonometry (1749), The elements of optics (1768) and The principles of mechanics (1754).[22]

Herschel took lessons from a local mirror-builder and having obtained both tools and a level of expertise, started building his own reflecting telescopes. He would spend up to 16 hours a day grinding and polishing the speculum metal primary mirrors. He relied on the assistance of other family members, particularly his sister Caroline and his brother Alexander, a skilled mechanical craftsperson.[22]

He "began to look at the planets and the stars"[24] in May 1773 and on 1 March 1774 began an astronomical journal by noting his observations of Saturn's rings and the Great Orion Nebula (M42).[22] The English Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne visited the Herschels while they were at Walcot (which they left on 29 September 1777).[25] By 1779, Herschel had also made the acquaintance of Sir William Watson, who invited him to join the Bath Philosophical Society.[22] Herschel became an active member, and through Watson would greatly enlarge his circle of contacts.[23][26] A few years later, in 1785, Herschel was elected an international member of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia.[27]

Double stars[edit]

Herschel's early observational work soon focused on the search for pairs of stars that were very close together visually. Astronomers of the era expected that changes over time in the apparent separation and relative location of these stars would provide evidence for both the proper motion of stars and, by means of parallax shifts in their separation, for the distance of stars from the Earth. The latter was a method first suggested by Galileo Galilei.[28] From the back garden of his house in New King Street, Bath, and using a 6.2-inch aperture (160 mm), 7-foot-focal-length (2.1 m) (f/13) Newtonian telescope "with a most capital speculum" of his own manufacture,[29] in October 1779, Herschel began a systematic search for such stars among "every star in the Heavens",[28]: 5 with new discoveries listed through 1792. He soon discovered many more binary and multiple stars than expected, and compiled them with careful measurements of their relative positions in two catalogues presented to the Royal Society in London in 1782 (269 double or multiple systems)[30] and 1784 (434 systems).[31] A third catalogue of discoveries made after 1783 was published in 1821 (145 systems).[32][33]

The Rev. John Michell of Thornhill published work in 1767 on the distribution of double stars,[34] and in 1783 on "dark stars", that may have influenced Herschel.[35] After Michell's death in 1793, Herschel bought a ten-foot-long, 30-inch reflecting telescope from Michell's estate.[36]

In 1797, Herschel measured many of the systems again, and discovered changes in their relative positions that could not be attributed to the parallax caused by the Earth's orbit. He waited until 1802 (in Catalogue of 500 new Nebulae, nebulous Stars, planetary Nebulae, and Clusters of Stars; with Remarks on the Construction of the Heavens) to announce the hypothesis that the two stars might be "binary sidereal systems" orbiting under mutual gravitational attraction, a hypothesis he confirmed in 1803 in his Account of the Changes that have happened, during the last Twenty-five Years, in the relative Situation of Double-stars; with an Investigation of the Cause to which they are owing.[28]: 8–9 In all, Herschel discovered over 800 confirmed[37] double or multiple star systems, almost all of them physical rather than optical pairs. His theoretical and observational work provided the foundation for modern binary star astronomy;[18]: 74 new catalogues adding to his work were not published until after 1820 by Friedrich Wilhelm Struve, James South and John Herschel.[38][39]

Uranus[edit]

In March 1781, during his search for double stars, Herschel noticed an object appearing as a disk. Herschel originally thought it was a comet or a stellar disc, which he believed he might actually resolve.[40] He reported the sighting to Nevil Maskelyne the Astronomer Royal.[41] He made many more observations of it, and afterwards Russian Academician Anders Lexell computed the orbit and found it to be probably planetary.[42][43]

Herschel agreed, determining that it must be a planet beyond the orbit of Saturn.[44] He called the new planet the "Georgian star" (Georgium sidus) after King George III, which also brought him favour; the name did not stick.[45] In France, where reference to the British king was to be avoided if possible, the planet was known as "Herschel" until the name "Uranus" was universally adopted. The same year, Herschel was awarded the Copley Medal and elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.[43] In 1782, he was appointed "The King's Astronomer" (not to be confused with the Astronomer Royal).[46]

On 1 August 1782 Herschel and his sister Caroline moved to Datchet (then in Buckinghamshire but now in Berkshire). There, he continued his work as an astronomer and telescope maker.[47] He achieved an international reputation for their manufacture, profitably selling over 60 completed reflectors to British and Continental astronomers.[48]

Deep sky surveys[edit]

From 1782 to 1802, and most intensively from 1783 to 1790, Herschel conducted systematic surveys in search of "deep-sky" or non-stellar objects with two 20-foot-focal-length (610 cm), 12-inch-aperture (30 cm) and 18.7-inch-aperture (47 cm) telescopes (in combination with his favoured 6-inch-aperture instrument). Excluding duplicated and "lost" entries, Herschel ultimately discovered over 2,400 objects defined by him as nebulae.[15] (At that time, nebula was the generic term for any visually diffuse astronomical object, including galaxies beyond the Milky Way, until galaxies were confirmed as extragalactic systems by Edwin Hubble in 1924.[49])

Herschel published his discoveries as three catalogues: Catalogue of One Thousand New Nebulae and Clusters of Stars (1786), Catalogue of a Second Thousand New Nebulae and Clusters of Stars (1789) and the previously cited Catalogue of 500 New Nebulae ... (1802). He arranged his discoveries under eight "classes": (I) bright nebulae, (II) faint nebulae, (III) very faint nebulae, (IV) planetary nebulae, (V) very large nebulae, (VI) very compressed and rich clusters of stars, (VII) compressed clusters of small and large [faint and bright] stars, and (VIII) coarsely scattered clusters of stars. Herschel's discoveries were supplemented by those of Caroline Herschel (11 objects) and his son John Herschel (1754 objects) and published by him as General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters in 1864. This catalogue was later edited by John Dreyer, supplemented with discoveries by many other 19th-century astronomers, and published in 1888 as the New General Catalogue (abbreviated NGC) of 7,840 deep-sky objects. The NGC numbering is still the most commonly used identifying label for these celestial landmarks.[15]: 418

He discovered NGC 12, NGC 13, NGC 14, NGC 16, NGC 23, NGC 24, NGC 7457 (work in progress).

Works with his sister Caroline[edit]

Following the death of their father, William suggested that Caroline join him in Bath, England. In 1772, Caroline was first introduced to astronomy by her brother.[45][50][51]

Caroline spent many hours polishing the mirrors of high performance telescopes so that the amount of light captured was maximized. She also copied astronomical catalogues and other publications for William. After William accepted the office of King's Astronomer to George III, Caroline became his constant assistant.[52]

In October 1783, a new 20-foot telescope came into service for William. During this time, William was attempting to observe and then record all of the observations. He had to run inside and let his eyes readjust to the artificial light before he could record anything, and then he would have to wait until his eyes were adjusted to the dark before he could observe again. Caroline became his recorder by sitting at a desk near an open window. William would shout out his observations and she would write them down along with any information he needed from a reference book.[53]

Caroline began to make astronomical discoveries in her own right, particularly comets. In 1783, William built her a small Newtonian reflector telescope, with a handle to make a vertical sweep of the sky. Between 1783 and 1787, she made an independent discovery of M110 (NGC 205), which is the second companion of the Andromeda Galaxy. During the years 1786–1797, she discovered or observed eight comets.[54] She found fourteen new nebulae[55] and, at her brother's suggestion, updated and corrected Flamsteed's work detailing the position of stars.[56][57] She also rediscovered Comet Encke in 1795.[54]

Caroline Herschel's eight comets were published between 28 August 1782 to 5 February 1787. Five of her comets were published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. William was even summoned to Windsor Castle to demonstrate Caroline's comet to the royal family. William recorded this phenomenon himself, terming it "My Sister's Comet." She wrote letters to the Astronomer Royal to announce the discovery of her second comet, and wrote to Joseph Banks upon the discovery of her third and fourth comets.[51]

The Catalogue of stars taken from Mr Flamsteed's observations contained an index of more than 560 stars that had not been previously included.[55][57] Caroline Herschel was honoured by the Royal Astronomical Society for this work in 1828.[58]

Caroline also continued to serve as William Herschel's assistant, often taking notes while he observed at the telescope.[59] For her work as William's assistant, she was granted an annual salary of £50 by George III. Her appointment made her the first female in England to be honoured with a government position.[60] It also made her the first woman to be given a salary as an astronomer.[61]

In June 1785, owing to damp conditions, William and Caroline moved to Clay Hall in Old Windsor. On 3 April 1786, the Herschels moved to a new residence on Windsor Road in Slough.[47] Herschel lived the rest of his life in this residence, which came to be known as Observatory House.[62] It was demolished in 1963.[63]

William Herschel's marriage in 1788 caused a lot of tension in the brother-sister relationship. Caroline has been referred to as a bitter, jealous woman who worshipped her brother and resented her sister-in-law for invading her domestic life. With the arrival of Mary, Caroline lost her managerial and social responsibilities in the household, and with them much of her status. Caroline destroyed her journals between the years 1788 to 1798, so her feelings during this period are not entirely known. According to her memoir, Caroline then moved to separate lodgings, but continued to work as her brother's assistant. When her brother and his family were away from their home, she would often return to take care of it for them. In later life, Caroline and Lady Herschel exchanged affectionate letters.[51]

Caroline continued her astronomical work after William's death in 1822. She worked to verify and confirm his findings as well as putting together catalogues of nebulae. Towards the end of her life, she arranged two-and-a-half thousand nebulae and star clusters into zones of similar polar distances. She did this so that her nephew, John, could re-examine them systematically. Eventually, this list was enlarged and renamed the New General Catalogue.[64] In 1828, she was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society for her work.[65]

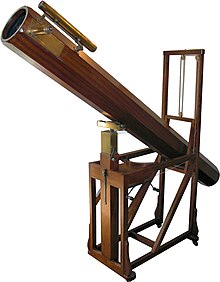

Herschel's telescopes[edit]

The most common type of telescope at that time was the refracting telescope, which involved the refraction of light through a tube using a convex glass lens. This design was subject to chromatic aberration, a distortion of an image due to the failure of light of different component wavelengths to converge. Optician John Dollond (1706–1761) tried to correct for this distortion by combining two separate lenses, but it was still difficult to achieve good resolution for far distant light sources.[45]

Reflector telescopes, invented by Isaac Newton in 1668, used a single concave mirror rather than a convex lens. This avoids chromatic aberration. The concave mirror gathered more light than a lens, reflecting it onto a flat mirror at the end of the telescope for viewing. A smaller mirror could provide greater magnification and a larger field of view than a convex lens. Newton's first mirror was 1.3 inches in diameter; such mirrors were rarely more than 3 inches in diameter.[45]

Because of the poor reflectivity of mirrors made of speculum metal, Herschel eliminated the small diagonal mirror of a standard newtonian reflector from his design and tilted his primary mirror so he could view the formed image directly. This "front view" design has come to be called the Herschelian telescope.[66][67]: 7

The creation of larger, symmetrical mirrors was extremely difficult. Any flaw would result in a blurred image. Because no one else was making mirrors of the size and magnification desired by Herschel, he determined to make his own.[45] This was no small undertaking. He was assisted by his sister Caroline and other family members. Caroline Herschel described the pouring of a 30-foot-focal-length mirror:

Herschel is reported to have cast, ground, and polished more than four hundred mirrors for telescopes, varying in size from 6 to 48 inches in diameter.[66][68] Herschel and his assistants built and sold at least sixty complete telescopes of various sizes.[66] Commissions for the making and selling of mirrors and telescopes provided Herschel with an additional source of income. The King of Spain reportedly paid £3,150 for a telescope.[51]

An essential part of constructing and maintaining telescopes was the grinding and polishing of their mirrors. This had to be done repeatedly, whenever the mirrors deformed or tarnished during use.[45] The only way to test the accuracy of a mirror was to use it.[66]

40ft telescope[edit]

The largest and most famous of Herschel's telescopes was a reflecting telescope with a 49½-inch-diameter (1.26 m) primary mirror and a 40-foot (12 m) focal length. The 40-foot telescope was, at that time, the largest scientific instrument that had been built. It was hailed as a triumph of "human perseverance and zeal for the sublimest science".[45][14]: 215

In 1785 Herschel approached King George for money to cover the cost of building the 40-foot telescope. He received £4,000.[69] Without royal patronage, the telescope could not have been created. As it was, it took five years, and went over budget.[45]

The Herschel home in Slough became a scramble of "labourers and workmen, smiths and carpenters".[45] A 40-foot telescope tube had to be cast of iron. The tube was large enough to walk through. Mirror blanks were poured from Speculum metal, a mix of copper and tin. They were almost four feet (1.2 m) in diameter and weighed 1,000 pounds (454 kg). When the first disk deformed due to its weight, a second thicker one was made with a higher content of copper. The mirrors had to be hand-polished, a painstaking process. A mirror was repeatedly put into the telescope and removed again to ensure that it was properly formed. When a mirror deformed or tarnished, it had to be removed, repolished and replaced in the apparatus. A huge rotating platform was built to support the telescope, enabling it to be repositioned by assistants as a sweep progressed. A platform near the top of the tube enabled the viewer to look down into the tube and view the resulting image.[45][69]

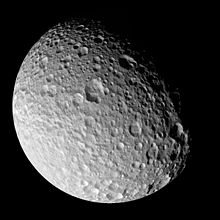

In 1789, shortly after this instrument was operational, Herschel discovered a new moon of Saturn: Mimas, only 250 miles (400 km) in diameter.[70] Discovery of a second moon (Enceladus) followed, within the first month of observation.[45][71][72]

The 40-foot (12.2-metre) telescope proved very cumbersome, and in spite of its size, not very effective at showing clearer images.[45] Herschel's technological innovations had taken him to the limits of what was possible with the technology of his day. The 40-foot would not be improved upon until the Victorians developed techniques for the precision engineering of large, high-quality mirrors.[73] William Herschel was disappointed with it.[45][66][74] Most of Herschel's observations were done with a smaller 18.5-inch (47 cm), 20-foot-focal-length (6.1 m) reflector. Nonetheless, the 40-foot caught the public imagination. It inspired scientists and writers including Erasmus Darwin and William Blake, and impressed foreign tourists and French dignitaries. King George was pleased.[45]

Herschel discovered that unfilled telescope apertures can be used to obtain high angular resolution, something which became the essential basis for interferometric imaging in astronomy (in particular aperture masking interferometry and hypertelescopes).[75]

Reconstruction of the 20-foot telescope[edit]

In 2012, the BBC television programme Stargazing Live built a replica of the 20-foot telescope using Herschel's original plans but modern materials. It is to be considered a close modern approximation rather than an exact replica. A modern glass mirror was used, the frame uses metal scaffolding and the tube is a sewer pipe. The telescope was shown on the programme in January 2013 and stands on the Art, Design and Technology campus of the University of Derby where it will be used for educational purposes.[76]

Life on other celestial bodies[edit]

Herschel was sure that he had found ample evidence of life on the Moon and compared it to the English countryside.[77] He did not refrain himself from theorising that the other planets were populated,[45] with a special interest in Mars, which was in line with most of his contemporary scientists.[77] During Herschel's time, scientists tended to believe in a plurality of civilised worlds; in contrast, most religious thinkers referred to unique properties of the earth.[77] Herschel went so far to speculate that the interior of the sun was populated.[77]

Sunspots, climate and wheat yields[edit]

Herschel examined the correlation of solar variation and solar cycle and climate.[78] Over a period of 40 years (1779–1818), Herschel regularly observed sunspots and their variations in number, form and size. Most of his observations took place in a period of low solar activity, the Dalton Minimum, when sunspots were relatively few in number. This was one of the reasons why Herschel was not able to identify the standard 11-year period in solar activity.[79][80] Herschel compared his observations with the series of wheat prices published by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations.[81]

In 1801, Herschel reported his findings to the Royal Society and indicated five prolonged periods of few sunspots correlated with the price of wheat.[78] Herschel's study was ridiculed by some of his contemporaries but did initiate further attempts to find a correlation. Later in the 19th century, William Stanley Jevons proposed the 11-year cycle with Herschel's basic idea of a correlation between the low number of sunspots and lower yields explaining recurring booms and slumps in the economy.[80]

Herschel's speculation on a connection between sunspots and regional climate, using the market price of wheat as a proxy, continues to be cited. According to one study, the influence of solar activity can actually be seen on the historical wheat market in England over ten solar cycles between 1600 and 1700.[79][80] The evaluation is controversial[82] and the significance of the correlation is doubted by some scientists.[83]

Further discoveries[edit]

| Uranus | 13 March 1781 |

| Oberon | 11 January 1787 |

| Titania | 11 January 1787 |

| Enceladus | 28 August 1789 |

| Mimas | 17 September 1789 |

In his later career, Herschel discovered two moons of Saturn, Mimas[71] and Enceladus;[72] as well as two moons of Uranus, Titania and Oberon.[84] He did not give these moons their names; they were named by his son John in 1847 and 1852, respectively, after his death.[71][72] Herschel measured the axial tilt of Mars[85] and discovered that the Martian ice caps, first observed by Giovanni Domenico Cassini (1666) and Christiaan Huygens (1672), changed size with that planet's seasons.[7] It has been suggested that Herschel discovered rings around Uranus.[86]

Herschel introduced but did not create the word "asteroid",[87] meaning star-like (from the Greek asteroeides, aster "star" + -eidos "form, shape"), in 1802 (shortly after Olbers discovered the second minor planet, 2 Pallas, in late March), to describe the star-like appearance of the small moons of the giant planets and of the minor planets; the planets all show discs, by comparison. By the 1850s 'asteroid' became a standard term for describing certain minor planets.[88]

From studying the proper motion of stars, the nature and extent of the solar motion was first demonstrated by Herschel in 1783, along with first determining the direction for the solar apex to Lambda Herculis, only 10° away from today's accepted position.[89][90][91]

Herschel also studied the structure of the Milky Way and was the first to propose a model of the galaxy based on observation and measurement.[92] He concluded that it was in the shape of a disk, but incorrectly assumed that the sun was in the centre of the disk.[93][94][95][96] This heliocentric view was eventually replaced by galactocentrism due to the work of Harlow Shapley, Heber Doust Curtis and Edwin Hubble in the 1900s. All three men used significantly more far-reaching and accurate telescopes than Herschel's.[93][94][97]

Discovery of infrared radiation in sunlight[edit]

In early 1800, Herschel was testing different filters to pass sunlight through, and noticed that filters of different colors seemed to generate varying amounts of heat. He decided to pass the light through a prism to measure the different colors of light using a thermometer,[6] and in the process, took a measurement just beyond the red end of the visible spectrum. He detected a temperature one degree higher than that of red light.[98] Further experimentation led to Herschel's conclusion that there must be an invisible form of light beyond the visible spectrum.[99][100] He published these results in April 1800.[98]

Biology[edit]

Herschel used a microscope to establish that coral was not a plant – as many at the time believed – because it lacked the cell walls characteristic of plants. It is in fact an animal, a marine invertebrate.[101]

Family and death[edit]

On 8 May 1788, William Herschel married the widow Mary Pitt (née Baldwin) at St Laurence's Church, Upton in Slough.[103] They had one child, John, born at Observatory House on 7 March 1792. William's personal background and rise as man of science had a profound impact on the upbringing of his son and grandchildren. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1788.[104] In 1816, William was made a Knight of the Royal Guelphic Order by the Prince Regent and was accorded the honorary title 'Sir' although this was not the equivalent of an official British knighthood.[105] He helped to found the Astronomical Society of London in 1820,[106] which in 1831 received a royal charter and became the Royal Astronomical Society.[107] In 1813, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

On 25 August 1822, Herschel died at Observatory House, Windsor Road, Slough, after a long illness. He was buried at nearby St Laurence's Church, Upton, Slough. Herschel's epitaph is

Caroline was deeply distressed by his death, and soon after his burial she returned to Hanover, a decision she later regretted. She had lived in England for fifty years. Her interests were much more in line with her nephew John Herschel, also an astronomer, than with her surviving family in Hanover. She continued to work on the organization and cataloguing of nebulae, creating what would later become the basis of the New General Catalogue. She died on 9 January 1848.[51][54][109]

Memorial[edit]

William Herschel lived most of his life in the town of Slough, then in Buckinghamshire (now in Berkshire). He died in the town and was buried under the tower of the Church of St Laurence, Upton-cum-Chalvey, near Slough.[110]

Herschel is especially honoured in Slough and there are several memorials to him and his discoveries. In 2011 a new bus station, the design of which was inspired by the infrared experiment of William Herschel, was built in the centre of Slough.[111]

His house at 19 New King Street in Bath, Somerset, where he made many telescopes and first observed Uranus, is now home to the Herschel Museum of Astronomy.[112]

There is a memorial near the choir screen in Westminster Abbey.[113]

Musical works[edit]

Herschel's complete musical works were as follows:[114]

- 18 symphonies for small orchestra (1760–1762)

- 6 symphonies for large orchestra (1762–1764)

- 12 concertos for oboe, violin and viola (1759–1764)

- 2 concertos for organ

- 6 sonatas for violin, cello and harpsichord (published 1769)

- 12 solos for violin and basso continuo (1763)

- 24 capriccios and 1 sonata for solo violin

- 1 andante for two basset horns, two oboes, two horns and two bassoons.

Various vocal works including a "Te Deum", psalms, motets and sacred chants along with some catches.

Keyboard works for organ and harpsichord:

- 6 fugues for organ

- 24 sonatas for organ (10 now lost)

- 33 voluntaries and pieces for organ (incomplete)

- 24 pieces for organ (incomplete)

- 12 voluntaries (11 now lost)

- 12 sonatas for harpsichord (9 extant)

- 25 variations on an ascending scale

- 2 minuets for harpsichord

Named after Herschel[edit]

- The astrological symbol for planet Uranus (

) features the capital initial letter of Herschel's surname.

) features the capital initial letter of Herschel's surname. - Mu Cephei is also known as Herschel's Garnet Star

- Herschel, a crater on the Moon

- Herschel, a large impact basin on Mars

- The enormous crater Herschel on Saturn's moon Mimas

- The Herschel gap in Saturn's rings.

- 2000 Herschel, an asteroid

- The William Herschel Telescope on La Palma

- The Herschel Space Observatory, successfully launched by the European Space Agency on 14 May 2009. It is the largest space telescope of its kind

- Herschel Grammar School, Slough

- Rue Herschel, a street in the 6th arrondissement of Paris.

- The Herschel Building at Bath College, Bath

- The Herschel building at Newcastle University, Newcastle, United Kingdom

- Herschel Museum of Astronomy, at 19 New King Street in Bath.

- Herschelschule, Hanover, Germany, a grammar school

- The Herschel Observatory, at the Universitas School in Santos, Brazil.

- The lunar crater C. Herschel, the asteroid 281 Lucretia, and the comet 35P/Herschel-Rigollet are named after his sister Caroline Herschel.

- The public house "Herschel Arms" at 22 Park Street, Slough is named after him and is quite close to the site of Observatory House.

- Herschel Astronomical Society, the operator of the Herschel Memorial Observatory based in Eton, Berkshire.

- Herschel Park, Slough.

- The shape of Slough Bus Station, built in 2011, was inspired by Herschel's infrared experiment.[111]

- Herschel Grammar School, Slough

See also[edit]

- Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars

- German inventors and discoverers

- List of astronomical instrument makers

- List of largest optical telescopes historically

- NGC 4800

- NGC 4694

References[edit]

- ^ Hoskin, Michael (June 2013). "The Herschel knighthoods under scrutiny". Astronomy & Geophysics. 54 (3): 3.23–3.24. doi:10.1093/astrogeo/att080.

- ^ a b Hoskin, Michael, ed. (2003). Caroline Herschel's autobiographies. Cambridge: Science History Publ. p. 13. ISBN 978-0905193069.

- ^ "William Herschel | Biography, Education, Telescopes, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ "Herschel". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ "Sir William Herschel | British-German astronomer".

- ^ a b "Herschel discovers infrared light". Cool Cosmos. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ a b "Mars in the Classroom". Copus. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Hoskin, M. (2004). "Was William Herschel a deserter?". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 35, Part 3 (120): 356–358. Bibcode:2004JHA....35..356H. doi:10.1177/002182860403500307. S2CID 117464495.

- ^ Clerke, Agnes M (1908). "A Popular History of Astronomy During the Nineteenth Century" (4 (republished as eBook number 28247) ed.). London (republished eText): Adam and Charles Black (republished Project Gutenberg): 18.

- ^ Holmes 2008, pp. 67.

- ^ Griffiths, Martin (18 October 2009). "Music(ian) of the spheres William Herschel and the astronomical revolution". LabLit. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ "Chan 10048 William Herschel (1738–1822)". Chandos. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ "Seagull city: Sunderland's literary and cultural heritage". Seagull city. 24 May 2017.

- ^ a b Lubbock, Constance Ann (1933). The Herschel Chronicle: The Life-story of William Herschel and His Sister, Caroline Herschel. CUP Archive. pp. 1–.

- ^ a b c Barentine, John C. (2015). The Lost Constellations: A History of Obsolete, Extinct, or Forgotten Star Lore. Springer. p. 410. ISBN 9783319227955.

- ^ Cowgill, Rachel; Holman, Peter, eds. (2007). Music in the British Provinces, 1690–1914. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 100–111. ISBN 9781351557313. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ Duckles, V. (1962). "Sir William Herschel as a Composer". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 74 (436): 55–59. Bibcode:1962PASP...74...55D. doi:10.1086/127756.

- ^ a b Macpherson, Hector Copland (1919). Herschel. London & New York: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge; Macmillan. p. 13. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ "Welcome to Herschel Museum of Astronomy". Herschel Museum of Astronomy. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ Hoskin, M. (1980), "Alexander Herschel: The forgotten partner", Journal for the History of Astronomy, 35 (4): 387–420, Bibcode:1980JHA....11..153H, doi:10.1177/002182868001100301, S2CID 115478560.

- ^ Schaarwächter, Jürgen (2015). Two Centuries of British Symphonism: From the beginnings to 1945. Olms: Verlag. ISBN 9783487152288. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Winterburn, E. (25 June 2014). "Philomaths, Herschel, and the myth of the self-taught man". Notes and Records. 68(3): 207–225. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2014.0027. PMC 4123665. PMID 25254276.

- ^ a b "Sir William Herschel British-German astronomer". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ Levy, David H. (1994). The Quest for Comets An Explosive Trail of Beauty and Danger. Boston, MA: Springer US. p. 38. ISBN 978-1489959980. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Hoskin, Michael (2012). The construction of the heavens : the cosmology of William Herschel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1107018389. Retrieved 6 June2018.

- ^ Ring, Francis (2012). "The Bath Philosophical Society and its influence on William Herschel's career" (PDF). Culture and Cosmos. 16: 45–42. doi:10.46472/CC.01216.0211. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Aitken, Robert Grant (1935). The Binary Stars. New York and London: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. pp. 4–9. ISBN 978-1117504094.

- ^ Mullaney 2007, p. 10

- ^ Herschel, Mr.; Watson, Dr. (1 January 1782). "Catalogue of Double Stars. By Mr. Herschel, F. R. S. Communicated by Dr. Watson, Jun". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 72: 112–162. Bibcode:1782RSPT...72..112H. doi:10.1098/rstl.1782.0014.

Read January 10, 1782

- ^ Herschel, W. (1 January 1785). "Catalogue of Double Stars. By William Herschel, Esq. F. R. S". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 75: 40–126. Bibcode:1785RSPT...75...40H. doi:10.1098/rstl.1785.0006. S2CID 186209747.

Read December 8, 1784

- ^ Herschel, W. (1821). "On the places of 145 new Double Stars". Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society. 1: 166. Bibcode:1822MmRAS...1..166H.

Read June 8, 1821

- ^ MacEvoy, Bruce. "The William Herschel Double Star Catalogs Restored". Astronomical Files from Black Oak Observatory. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Heintz, Wulff D. (1978). Double stars. Dordrecht: Reidel. p. 4. ISBN 9789027708854. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ Schaffer, Simon (1979). "John Mitchell and Black Holes". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 10: 42–43. Bibcode:1979JHA....10...42S. doi:10.1177/002182867901000104. S2CID 123958527. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ Geikie, Archibald (2014). Memoir of John Michell. Cambridge University Press. pp. 12–18, 95–96. ISBN 9781107623781. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ William Herschel's Double Star Catalog. Handprint.com (5 January 2011). Retrieved on 5 June 2011.

- ^ North, John (2008). Cosmos : an illustrated history of astronomy and cosmology. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226594415. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Cavin, Jerry D. (2011). The Amateur Astronomer's Guide to the Deep-sky Catalogs. New York: Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-1-4614-0655-6. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Holmes 2008, pp. 96.

- ^ Raffael, Michael (2006). Bath Curiosities. Birlinn. p. 38. ISBN 978-1841585031.

- ^ Kuhn, Thomas S. (1970). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0226458045.

- ^ a b Schaffer, Simon (1981). "Uranus and the Establishment of Herschel's Astronomy". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 12: 11–25. Bibcode:1981JHA....12...11S. doi:10.1177/002182868101200102. S2CID 118813550.

- ^ Astronomical League National – Herschel Club – Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel. Astroleague.org. Retrieved on 5 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Roberts, Jacob (2017). "A Giant of Astronomy". Distillations. 3 (3): 6–11.

- ^ Clerke, Agnes Mary (1901). The Herschels and modern astronomy. Cambridge: New York. pp. 30–35. ISBN 978-1108013925.

- ^ a b Holden, Edward S. (1881). . New York: Charles Scribner's Sons – via Wikisource.

- ^ Mullaney 2007, p. 14

- ^ Alfred, Randy (30 December 2009). "Dec. 30, 1924: Hubble Reveals We Are Not Alone". Wired. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ esa. "Caroline and William Herschel: Revealing the invisible". European Space Agency. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Herschel, Caroline (1876). Herschel, Mrs. John (ed.). Memoir and Correspondence of Caroline Herschel. London: John Murray, Albermarle Street.

- ^ Fernie, J. Donald (November–December 2007). The Inimitable Caroline. American Scientist. pp. 486–488.

- ^ Hoskin, Michael (2011). Discoverers of the Universe: William and Caroline Herschel. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691148335.

- ^ a b c Olson, Roberta J. M.; Pasachoff, Jay M. (2012). "The Comets of Caroline Herschel (1750–1848), Sleuth of the Skies at Slough". Culture and Cosmos. 16: 53–80. arXiv:1212.0809. Bibcode:2012arXiv1212.0809O. doi:10.46472/CC.01216.0213. S2CID 117934098.

- ^ a b Redd, Nola Taylor (4 September 2012). "Caroline Herschel Biography". Space.com.

- ^ Ogilvie, Marilyn Bailey (2008). Searching the stars. Stroud: Tempus. p. 146. ISBN 9780752442778. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ a b Herchsel, Caroline; Flamsteed, John (1798). Catalogue of stars taken from Mr Flamsteed's observations contained in the second volume of the Historia Coelestis and not inserted in the British catalogue ... / by Carolina Herschel; with notes & introduction by William Herchsel. London: Sold by Peter Elmsly, printer to the Royal society. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Holmes 2008, pp. 410.

- ^ Baldwin, Emily. "Caroline Herschel (1750–1848)". www.sheisanastronomer.org. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ Ogilvie, Marilyn Bailey (1986). Women in Science: Antiquity Through the Nineteenth Century. MIT Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-0-262-65038-0.

- ^ Zielinski, Sarah. "Caroline Herschel: Assistant or Astronomer?". smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "Astronomical observatory". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ "Observatory House, about 1900". Slough House Online. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Herschel, J. F. W. (1863–1864). "A General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars for the Year 1860.0, with Precessions for 1880.0". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 13: 1–3. Bibcode:1863RSPS...13....1H. JSTOR 111986.

- ^ "Awards, Medals and Prizes Winners of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society". Royal Astronomical Society. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 5 June2018.

- ^ a b c d e Maurer, A.; Forbes, E. G. (1971). "William Herschel's Astronomical Telescopes". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 81: 284–291. Bibcode:1971JBAA...81..284M.

- ^ Bratton, Mark (2011). The complete guide to the Herschel objects : Sir William Herschel's star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 9780521768924. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Hastings, C. S. (1891). "History of the telescope". The Sidereal Messenger: A Monthly Review of Astronomy. 10: 342. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ a b "40-foot Herschelian (reflector) telescope tube remains – National Maritime Museum". Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Holmes 2008, pp. 190.

- ^ a b c "Mimas". NASA Science Solar System Exploration. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ a b c "Enceladus". NASA Science Solar System Exploration. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Chapman, A. (1989). "William Herschel and the Measurement of Space". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 30(4): 399. Bibcode:1989QJRAS..30..399C.

- ^ Ceragioli, R. (2018). "William Herschel and the "Front-View" Telescopes". In Cunningham, C. (ed.). The Scientific Legacy of William Herschel. Historical & Cultural Astronomy. Cham: Springer. pp. 97–238. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32826-3_4. ISBN 978-3-319-32825-6.

- ^ Baldwin, J. E.; Haniff, C. A. (15 May 2002). "The application of interferometry to optical astronomical imaging". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 360 (1794): 969–986. Bibcode:2002RSPTA.360..969B. doi:10.1098/rsta.2001.0977. PMID 12804289. S2CID 21317560.

- ^ "BBC builds William Herschel's telescope for Stargazing Live". BBC/Ariel. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d Basalla, George (2006). Civilized life in the universe : scientists on intelligent extraterrestrials. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 52. ISBN 9780195171815.

- ^ a b Herschel, W. (1801). "Observations tending to investigate the nature of the Sun, in order to find the causes or symptoms of its variable emission of light and heat; With remarks on the use that may possibly be drawn from solar observations". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 91: 265–318. Bibcode:1801RSPT...91..265H. doi:10.1098/rstl.1801.0015. JSTOR 107097.

- ^ a b Ball, Philip (22 December 2003). "Sun set food prices in the Middle Ages". Nature. doi:10.1038/news031215-12. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Pustil'nik, Lev A.; Din, Gregory Yom (September 2004). "Influence of solar activity on the state of the wheat market in medieval England". Solar Physics. 223 (1–2): 335–356. arXiv:astro-ph/0312244. Bibcode:2004SoPh..223..335P. doi:10.1007/s11207-004-5356-5. S2CID 55852885.

- ^ Nye, Mary Jo (2003). The Cambridge History of Science: Volume 5, The Modern Physical and Mathematical Sciences. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 508. ISBN 978-0521571999.

- ^ Lockwood, Mike (2012). "Solar Influence on Global and Regional Climates". Surveys in Geophysics. 33 (3–4): 503–534. Bibcode:2012SGeo...33..503L. doi:10.1007/s10712-012-9181-3.

- ^ Love, J. J. (2013). "On the insignificance of Herschel's sunspot correlation" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 40 (16): 4171–4176. Bibcode:2013GeoRL..40.4171L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.377.257. doi:10.1002/grl.50846.

- ^ Franz, Julia (1 January 2017). "Why the moons of Uranus are named after characters in Shakespeare". Studio 360.

- ^ "All About Mars". NASA Mars Exploration. Retrieved 5 June2018.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (18 April 2007). "Uranus rings 'were seen in 1700s'". BBC News.

- ^ In an oral presentation ("HAD Meeting with DPS, Denver, October 2013 – Abstracts of Papers". Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2013.), Clifford Cunningham presented his finding that the word has been coined by Charles Burney, Jr., the son of a friend of Herschel, see "Local expert reveals who really coined the word 'asteroid'". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. 8 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.. See also Wall, Mike (10 January 2011). "Who Really Invented the Word 'Asteroid' for Space Rocks?". SPACE.com. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ Williams, Matt (24 August 2015). "What is the asteroid belt?". Universe Today.

- ^ Lankford, John (1997). History of astronomy: an encyclopedia. Garland encyclopedias in the history of science. 1. Taylor & Francis. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-8153-0322-0.

- ^ Herschel, William (1783). "On the Proper Motion of the Sun and Solar System; With an Account of Several Changes That Have Happened among the Fixed Stars since the Time of Mr. Flamstead [sic]". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 73: 247–83. doi:10.1098/rstl.1783.0017. JSTOR 106492. S2CID 186213288.

- ^ Hoskin, M. (1980), "Herschel's Determination of the Solar Apex", Journal for the History of Astronomy, 11 (3): 153–163, Bibcode:1980JHA....11..153H, doi:10.1177/002182868001100301, S2CID 115478560.

- ^ Herschel, William (1 January 1785). "XII. On the construction of the heavens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 75: 213–266. doi:10.1098/rstl.1785.0012. S2CID 186213203.

- ^ a b van de Kamp, Peter (October 1965), "The Galactocentric Revolution, A Reminiscent Narrative", Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 77 (458): 324–328, Bibcode:1965PASP...77..325V, doi:10.1086/128228

- ^ a b Berendzen, Richard (1975). "Geocentric to heliocentric to galactocentric to acentric: the continuing assault to the egocentric". Vistas in Astronomy. 17 (1): 65–83. Bibcode:1975VA.....17...65B. doi:10.1016/0083-6656(75)90049-5.

- ^ "The Shape of the Milky Way from Starcounts". Astro 801. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Stargazers in History, PBS

- ^ Bergh, Sidney van den (2011). "Hubble and Shapley—Two Early Giants of Observational Cosmology". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 105 (6): 245. arXiv:1110.2445. Bibcode:2011JRASC.105..245V.

- ^ a b Herschel, William (1800). "Experiments on the refrangibility of the invisible rays of the Sun". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 90: 284–292. doi:10.1098/rstl.1800.0015. JSTOR 107057.

- ^ Rowan-Robinson, Michael (2013). Night Vision: Exploring the Infrared Universe. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 9781107024762. OCLC 780161457.

- ^ Aughton, Peter (2011). The story of astronomy. New York: Quercus. ISBN 978-1623653033. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Azzouni, Jody (20 July 2017). Ontology Without Borders. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190622558.

- ^ George Thomas Clark (1809–1898), article on heraldry in the Encyclopaedia Britannica (9th & 10th editions)[1]

- ^ Holmes 2008, pp. 186.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter H" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ Hanham, A. & Hoskin, M. (2013). "The Herschel Knighthoods: Facts and Fiction". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 44 (120): 149–164. Bibcode:2013JHA....44..149H. doi:10.1177/002182861304400202. S2CID 118171124.

- ^ Shortland, E. (1820). "The Astronomical Society of London". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 81: 44–47. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "A brief history of the RAS". Royal Astronomical Society. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ Pendergrast, Mark (2004). Mirror mirror : a history of the human love affair with reflection. New York: Basic Books. p. 159. ISBN 978-0465054718. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Caroline Herschel Biography". Space.com. 4 September 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ "Our History". Saint Laurence Church, Upton-cum-Chalvey, Slough. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ a b Serck, Linda (28 May 2011). "Slough bus station: Silver dolphin or beached whale?". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 13 August2012.

- ^ "Visiting". Herschel Museum of Astronomy. Retrieved 6 June2018.

- ^ 'The Abbey Scientists' Hall, A.R. p53: London; Roger & Robert Nicholson; 1966

- ^ "William Herschel (1738–1822): Organ works". asterope.bajaobs.hu. Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

Sources[edit]

- Holden, Edward S. (1881). . New York: Charles Scribner's Sons – via Wikisource.

- Holmes, Richard (2008). The age of wonder. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-1-4000-3187-0.

- Mullaney, James (2007). The Herschel objects and how to observe them. ISBN 978-0-387-68124-5. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

Further reading[edit]

- "William Herschel" by Michael Hoskin. New Dictionary of Scientific Biography Scribners, 2008. v. 3, pp. 289–291.

- Biography: JRASC 74 (1980) 134

External links[edit]

| Library resources about William Herschel |

| By William Herschel |

|---|

Media related to Wilhelm Herschel at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wilhelm Herschel at Wikimedia Commons

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: William Herschel |

Works written by or about William Herschel at Wikisource

Works written by or about William Herschel at Wikisource- Articles and letters published in the Philosophical Transactions and available online (70 items, June 2016)

- William Herschel's Deep Sky Catalog

- The William Herschel Double Star Catalogs Restored

- Full text of

Herschel by Hector Macpherson.

Herschel by Hector Macpherson. - Full text of The Story of the Herschels (1886) from Project Gutenberg

- Portraits of William Herschel at the National Portrait Gallery (United Kingdom)

- Herschel Museum of Astronomy located in his Bath home

- William Herschel Society

- The Oboe Concertos of Sir William Herschel, Wilbert Davis Jerome ed. ISBN 0-87169-225-2

- Works by or about William Herschel in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- A notebook of Herschel's, dated from 1759 Archived 9 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine is available in the digital collections of the Linda Hall Library.

- Portraits of William Herschel (and other members of the family) from the Lick Observatory Records Digital Archive, UC Santa Cruz Library's Digital Collections Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Michael Lemonick: William Herschel, the First Observational Cosmologist, 12 November 2008, Fermilab Colloquium, Text

- Free scores by William Herschel at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Musical pieces by William Herschel @YouTube:

- Chamber Symphony in F minor No. 4- Allegro moderato (I) on YouTube

- Hubble Images to Herschel Music on YouTube (Chamber Symphony in F, 2nd movement)

- Richmond Sinfonia for Strings, Bassoon & Harpsichord n. 2 in D major on YouTube

- Sinfonía para Cuerdas No. 8 en Do menor on YouTube

- Sinfonia n. 12, primo movimento, Allegro on YouTube

- Symphony No. 8, I: Allegro Assai on YouTube

Caroline Herschel

Caroline Herschel | |

|---|---|

Caroline Herschel at 78, one year after winning the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1828 | |

| Born | Caroline Lucretia Herschel 16 March 1750 |

| Died | 9 January 1848 (aged 97) Hanover, Kingdom of Hanover, German Confederation |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Discovery of several comets |

| Awards | Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1828) Prussian Gold Medal for Science (1846) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

Caroline Lucretia Herschel (/ˈhɜːrʃəl, ˈhɛər-/;[1] 16 March 1750 – 9 January 1848) was a German astronomer, whose most significant contributions to astronomy were the discoveries of several comets, including the periodic comet 35P/Herschel–Rigollet, which bears her name.[2] She was the younger sister of astronomer William Herschel, with whom she worked throughout her career.

She was the first woman to receive a salary as a scientist.[3] She was the first woman in England to hold a government position.[4] She was the first woman to publish scientific findings in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society,[5] to be awarded a Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1828), and to be named an Honorary Member of the Royal Astronomical Society (1835, with Mary Somerville). She was also named an honorary member of the Royal Irish Academy (1838). The King of Prussia presented her with a Gold Medal for Science on the occasion of her 96th birthday (1846).[6]

Early life[edit]

Caroline Lucretia Herschel was born in the town of Hanover on 16 March 1750. She was the eighth child and fourth daughter of Issak Herschel, a self-taught oboist, and his wife, Anna Ilse Moritzen. The Herschel family originated from Pirna in Saxony near Dresden. Issak became a bandmaster in the Hanoverian Foot Guards, whom he first joined in 1731, and was away with his regiment for substantial periods. He became ill after the Battle of Dettingen (part of the War of the Austrian Succession) in 1743 and never recovered fully; he suffered a weak constitution, chronic pain, and asthma for the remainder of his life.[6][7][8] The oldest of their daughters, Sophia, was sixteen years older, and the only surviving girl besides Caroline. She married when Caroline was five, meaning that the younger girl was tasked with much of the household drudgery.[9] Caroline and the other children received a cursory education, learning to read and write and little more. Her father attempted to educate her at home, but his efforts were mostly successful with the boys.[8]

At the age of ten, Caroline was struck with typhus, which stunted her growth, such that she never grew taller than 4 feet 3 inches (1.30 m).[2] She suffered vision loss in her left eye as a result of her illness.[8] Her family assumed that she would never marry and her mother felt it was best for her to train to be a house servant[10] rather than becoming educated in accordance with her father's wishes. Her father sometimes took advantage of her mother's absence by tutoring her individually, or including her in her brother's lessons, such as violin. Caroline was briefly allowed to learn dress-making. Though she learned to do needlework from a neighbour, her efforts were stymied by long hours of household chores.[6][11] To prevent her from becoming a governess and earning her independence that way, she was forbidden to learn French or more advanced needlework than what she could pick up from neighbours.[7]

Following her father's death, her brothers William and Alexander proposed that she join them in Bath, England to have a trial period as a singer for musician brother William's church performances.[6][7] Caroline eventually left Hanover on 16 August 1772 after her brother's intervention with their recalcitrant mother.[7][11] On the journey to England, she was first introduced to astronomy by way of the constellations and opticians' shops.[7]

In Bath, she took on the responsibilities of running William's household, and began learning to sing.[11] William had established himself as an organist and music teacher at 19 New King Street, Bath (now the Herschel Museum of Astronomy). He was also the choirmaster of the Octagon Chapel.[8] William was busy with his musical career and became fairly busy organising public concerts.

Caroline did not blend in with the local society and made few friends,[12] but was finally able to indulge her desire to learn, and took regular singing, English, and arithmetic lessons from her brother, and dance lessons from a local teacher.[11] She also learned to play the harpsichord, and eventually became an integral part in William's musical performances at small gatherings.[13] She became the principal singer at his oratorio concerts, and acquired such a reputation as a vocalist that she was offered an engagement for the Birmingham festival[14] after a performance of Handel's Messiah in April 1778, where she was the first soloist. She declined to sing for any conductor but William, and after that performance, her career as a singer began to decline. Caroline was subsequently replaced as a performer by distinguished soloists from outside the area because William wished to spend less time in rehearsals to focus on astronomy.[7][8]

Transition to astronomy[edit]

When William became increasingly interested in astronomy, transforming himself from a musician to an astronomer, Caroline again supported his efforts. She said somewhat bitterly, in her Memoir, "I did nothing for my brother but what a well-trained puppy dog would have done, that is to say, I did what he commanded me." Ultimately, though, she became interested in astronomy and enjoyed her work.[6] In the 1770s, as William became more interested in astronomy, he started to build his own telescopes from lenses he had ground, unhappy with the quality of lenses he was able to purchase. Caroline would feed him and read to him as he worked, despite her desire to burnish her career as a professional singer.[7] She became a significant astronomer in her own right as a result of her collaboration with him.[2] The Herschels moved to a new house in March 1781 after their millinery business failed, and Caroline was guarding the leftover stock on 13 March, the night that William discovered the planet Uranus. Though he mistook it for a comet, his discovery proved the superiority of his new telescope. Caroline and William gave their last musical performance in 1782, when her brother accepted the private office of court astronomer to King George III; the last few months of their musical career had been a shambles and were critically panned.[7][15]

Astronomical career[edit]

First discoveries and catalogue[edit]

William's interest in astronomy started as a hobby to pass time at night. At breakfast the next day he would give an impromptu lecture on what he had learned the night before. Caroline became as interested as William, stating that she was "much hindered in my practice by my help being continually wanted in the execution of the various astronomical contrivances."[12] William became known for his work on high performance telescopes, and Caroline found herself supporting his efforts. Caroline spent many hours polishing mirrors and mounting telescopes in order to maximize the amount of light captured.[16] She learned to copy astronomical catalogues and other publications that William had borrowed. She also learned to record, reduce, and organize her brother's astronomical observations.[17] She recognized that this work demanded speed, precision and accuracy.[18]

Caroline was asked to move from the high culture of Bath to the relative backwater of Datchet in 1782, a small town near Windsor Castle where William would be on hand to entertain royal guests. He presumed that Caroline would become his assistant, a role she did not initially accept. She was unhappy with the accommodations they had taken; the house they rented for three years had a leaky ceiling and Caroline described it as "the ruins of a place". She was also aghast at the prices in the city and the fact that their domestic servant was imprisoned for theft at the time of her arrival. While William worked on a catalogue of 3,000 stars, studied double stars, and attempted to discover the cause of Mira's and Algol's variability, Caroline was asked to "sweep" the sky, meticulously moving through the sky in strips to search for interesting objects. She was unhappy with this task at the beginning of her work, longing for the culture of Bath and feeling isolated and lonely, but gradually developed a love for the work.[7]

On 28 August 1782 Caroline initiated her first record book. She inscribed the first three opening pages: "This is what I call the Bills & Rec.ds of my Comets",[a] "Comets and Letters", and "Books of Observations". This, along with two subsequent books, currently belong to the Herschel trove at the Royal Astronomical Society in London.[20]

On 26 February 1783, Caroline made her first discovery: she had found a nebula that was not included in the Messier catalogue. That same night, she independently discovered Messier 110 (NGC 205), the second companion of the Andromeda Galaxy. William then began to search himself for nebulae, sensing that there were many discoveries to be made. Caroline was relegated to a ladder on William's 20-foot reflector, attempting impossible measurements of double stars. William quickly realized his method of searching for nebulae was inefficient and he required an assistant to keep records. Naturally, he turned to Caroline.[7][11]

In the summer of 1783, William finished building a comet-searching telescope for Caroline, which she began to use immediately.[11] Beginning in October 1783, the Herschels used a 20-foot reflecting telescope to search for nebulae. Initially, William attempted to both observe and record objects, but this too was inefficient and he again turned to Caroline. She sat by a window inside, William shouted his observations, and Caroline recorded. This was not a simple clerical task, however, because she would have to use John Flamsteed's catalogue to identify the star William used as a reference point for the nebulae. Because Flamsteed's catalogue was organized by constellation, it was less useful to the Herschels, so Caroline created her own catalogue organized by north polar distance.[7][21] The following morning, Caroline would go over her notes and write up formal observations, which she called "minding the heavens."[20]

Comets[edit]

During 1786–97 she discovered eight comets, the first on 1 August 1786 while her brother was away and she was using his telescope.[5] She had unquestioned priority as discoverer of five of the comets[3][5][22] and rediscovered Comet Encke in 1795.[23] Five of her comets were published in Philosophical Transactions. A packet of paper bearing the superscription, "This is what I call the Bills and Receipts of my Comets" contains some data connected with the discovery of each of these objects. William was summoned to Windsor Castle to demonstrate Caroline's comet to the royal family. William recorded this phenomenon, himself, terming it "My Sister's Comet."[24] Caroline Herschel is often credited as the first woman to discover a comet; however, Maria Kirch discovered a comet in the early 1700s, but is often overlooked because at the time, the discovery was attributed to her husband, Gottfried Kirch.[8]

She wrote a letter to the Astronomer Royal to announce the discovery of her second comet. The third comet was discovered on 7 January 1790, and the fourth one on 17 April 1790. She announced both of these to Sir Joseph Banks, and all were discovered with her 1783 telescope.[25] In 1791, Caroline began to use a 9-inch telescope for her comet-searching, and discovered three more comets with this instrument.[11] Her fifth comet was discovered on 15 December 1791 and the sixth on 7 October 1795. Caroline wrote in her journal during this time "My brother wrote an account of it to Sir J. Banks, Dr. Maskelyne, and to several astronomical correspondents" for the discovery of her fifth comet. Two years later, her eighth and last comet was discovered on 6 August 1797, the only comet she discovered without optical aid.[11][25] She announced this discovery by sending a letter to Banks.[25] In 1787, she was granted an annual salary of £50 (equivalent to £6,500 in 2021[26]) by George III for her work as William's assistant.[14] Caroline's appointment made her the first woman in England honored with an official government position, and the first woman to be paid for her work in astronomy.[4][9]

In 1797 William's observations had shown that there were a great many discrepancies in the star catalogue published by John Flamsteed, which was difficult to use because it had been published as two volumes, the catalogue proper and a volume of original observations, and contained many errors. William realised that he needed a proper cross-index to properly explore these differences but was reluctant to devote time to it at the expense of his more interesting astronomical activities. He therefore recommended to Caroline that she undertake the task, which ultimately took 20 months. The resulting Catalogue of Stars, Taken from Mr. Flamsteed's Observations Contained in the Second Volume of the Historia Coelestis, and Not Inserted in the British Catalogue[27] was published by the Royal Society in 1798 and contained an index of every observation of every star made by Flamsteed, a list of errata, and a list of more than 560 stars that had not been included.[4][11] In 1825, Caroline donated the works of Flamsteed to the Royal Academy of Göttingen.[28]

Relationship with William[edit]

Throughout her writings, she repeatedly made it clear that she desired to earn an independent wage and be able to support herself. When the crown began paying her for her assistance to her brother in 1787, she became the first woman—at a time when even men rarely received wages for scientific enterprises—to receive a salary for services to science.[3] Her pension was £50 a year, and it was the first money that Caroline had ever earned in her own right.[11]

When William married a rich widow, Mary Pitt (née Baldwin) in 1788, the union caused tension in the brother-sister relationship. Caroline has been referred to as a bitter, jealous woman who worshipped her brother and resented those who invaded their domestic lives.[29] In his book The Age of Wonder, Richard Holmes is more sympathetic to Caroline's position, noting that the change was in many respects negative for Caroline. With the arrival of William's wife, Caroline lost her managerial and social responsibilities in the household and accompanying status. She also moved from the house to external lodgings, returning daily to work with her brother. She no longer held the keys to the observatory and workroom, where she had done much of her own work. Because she destroyed her journals from 1788 to 1798, her feelings about the period are not entirely known. In August 1799, Caroline was independently recognized for her work, when she spent a week in Greenwich as a guest of the royal family.[11]

Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond indicated she and her brother continued working well during this period. When her brother and his family were away from home, she often returned there to take care of it for them. In later life, she and Lady Herschel exchanged affectionate letters, and she became deeply attached to her nephew, astronomer John Herschel.[6][11]

William's marriage likely led to Caroline becoming more independent of her brother and more a figure in her own right.[30] Caroline made many discoveries independently of William and continued to work solo on many of the astronomical projects which contributed to her rise to fame.

New General Catalogue[edit]

In 1802, the Royal Society published Caroline's catalogue in its Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A under William's name. This listed around 500 new nebulae and clusters to the already known 2,000.[20] Toward the end of Caroline's life, she arranged two-and-a-half thousand nebulae and star clusters into zones of similar polar distances so that her nephew, John Herschel, could re-examine them systematically. The list was eventually enlarged and renamed the New General Catalogue. Many non-stellar objects are still identified by their NGC number.[31]

Later life and legacy[edit]

After her brother died in 1822, Caroline was grief-stricken and moved back to Hanover, Germany, continuing her astronomical studies to verify and confirm William's findings and producing a catalogue of nebulae to assist her nephew John Herschel in his work. However, her observations were hampered by the architecture in Hanover, and she spent most of her time working on the catalogue.[11] In 1828 the Royal Astronomical Society presented her with their Gold Medal for this work—no woman would be awarded it again until Vera Rubin in 1996.[32] Upon William's death, her nephew, John Herschel, took over observing at Slough. Caroline had given him his first introduction into astronomy, when she showed him the constellations in Flamsteed's Atlas. Caroline added her final entry to her observing book on 31 January 1824 about the Great Comet of 1823, which had already been discovered on 29 December 1823.[20] Throughout the twilight of her life, Caroline remained physically active and healthy, and regularly socialized with other scientific luminaries.[11] She spent her last years writing her memoirs and lamenting her body's limitations, which kept her from making any more original discoveries.[9]

Caroline Herschel died peacefully in Hanover on 9 January 1848. She is buried at 35 Marienstrasse in Hanover at the cemetery of the Gartengemeinde, next to her parents and with a lock of William's hair.[11] Her tombstone inscription reads, "The eyes of her who is glorified here below turned to the starry heavens."[31] With her brother, she discovered over 2,400 astronomical objects over twenty years.[11] The asteroid 281 Lucretia (discovered 1888) was named after Caroline's second given name,[33] and the crater C. Herschel on the Moon is named after her.[34]

Adrienne Rich's 1968 poem "Planetarium" celebrates Caroline Herschel's life and scientific achievements.[35] The artwork The Dinner Party, which celebrates historical women who have made extraordinary contributions, features a place setting for Caroline Herschel.[36] Google honoured her with a Google Doodle on her 266th birthday (16 March 2016).[37]

Honours[edit]

Herschel was honoured by the King of Prussia and the Royal Astronomical Society.[18] The gold medal from the Astronomical Society was awarded to her in 1828 "for her recent reduction, to January, 1800, of the [2,500] Nebulæ discovered by her illustrious brother, which may be considered as the completion of a series of exertions probably unparalleled either in magnitude or importance in the annals of astronomical labour." She completed this work after her brother's death and her move to Hanover.[6][22][38]

The Royal Astronomical Society elected her an Honorary Member in 1835,[14] along with Mary Somerville; they were the first women members. She was also elected as an honorary member of the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin in 1838.[9]

In 1846, at the age of 96, she was awarded a Gold Medal for Science by the King of Prussia, conveyed to her by Alexander von Humboldt, "in recognition of the valuable services rendered to Astronomy by you, as the fellow-worker of your immortal brother, Sir William Herschel, by discoveries, observations, and laborious calculations".[6]

Asteroid 281 Lucretia is named in her honor.[39]

The open clusters NGC 2360 (Caroline's Cluster)[40] and NGC 7789 (Caroline's Rose)[41] are named in her honor.

On 6 November 2020, a satellite named after her (ÑuSat 10 or "Caroline", COSPAR 2020-079B) was launched into space.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ According to astronomer John Louis Emil Dreyer, "Rec.ds" probably means Records.[19]

Citations[edit]

- ^ "Herschel". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ a b c Nysewander, Melissa. Caroline Herschel. Biographies of Women Mathematicians, Atlanta: Agnes Scott College, 1998.

- ^ a b c Brock, Claire (2004). "Public Experiments". History Workshop Journal. Oxford University Press. 58 (58): 306–312. doi:10.1093/hwj/58.1.306. JSTOR 25472768. S2CID 201783390.

- ^ a b c Ogilvie, Marilyn Bailey (1986). Women in Science: Antiquity through the Nineteenth Century. MIT Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-0-262-65038-0.

- ^ a b c Schiebinger, Londa (1989). The mind has no sex?: women in the origins of modern science. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 263.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Herschel, Caroline Lucretia (1876). Herschel, Mrs. John (ed.). Memoir and Correspondence of Caroline Herschel. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hoskin, Michael (2014). William and Caroline Herschel:Pioneers in Late 18th-Century Astronomy. SpringerBriefs in Astronomy. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6875-8. ISBN 978-94-007-6874-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Ogilvie, Marilyn B. (8 November 2011). Searching the Stars: The Story of Caroline Herschel. History Press. ISBN 9780752475462.

- ^ a b c d Brock, Claire (1 January 2007). The Comet Sweeper: Caroline Herschel's Astronomical Ambition. Icon. ISBN 9781840467208.

- ^ Roberts, Jacob (2017). "A Giant of Astronomy". Distillations. 3(3): 6–11. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Hoskin, Michael. "Herschel, Caroline Lucretia". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13100.(Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Fernie, J. Donald (November–December 2007), "The Inimitable Caroline", American Scientist, pp. 486–488

- ^ "Caroline Lucretia Herschel Facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Caroline Lucretia Herschel". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Lemonick, Michael (2009). The Georgian Star: How William and Caroline Herschel Revolutionized Our Understanding of the Cosmos. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-393-33709-9.

- ^ Ashworth, Wilhelm. "Untitled Review." The British Society for the History of Science Vol. 37 No. 3, 2004: 350–351.

- ^ "Letter from Caroline Herschel (Upton) to Margaret Maskelyne (at Greenwich)". Cambridge Digital Library. Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ a b Warner, Deborah. "Review, Untitled." Chicago Journal, 2004: 505.

- ^ Herschel, William (2013). Dreyer, John Louis Emil (ed.). The Scientific Papers of Sir William Herschel. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. xlv. ISBN 9781108064620.

- ^ a b c d Olson, Roberta J. M.; Pasachoff, Jay M. (2012). "The Comets of Caroline Herschel (1750–1848), Sleuth of the Skies at Slough". Culture and Cosmos. 16 (1–2): 9. arXiv:1212.0809. Bibcode:2012arXiv1212.0809O. doi:10.46472/CC.01216.0213. S2CID 117934098.

- ^ a b Hoskin, Michael (2011). Discoverers of the Universe: William and Caroline Herschel. Princeton University Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-1-4008-3812-7.